Introduction

There is much discussion on how to store and transport hydrogen, with diverse methods being proposed. I will focus on the storage and transportation at massive (i.e. infrastructure) scale.

Hydrogen Transportation

At massive scale, there are two principal ways to transport hydrogen: pipeline and ship. But this can be done as hydrogen, or as another carrier such as ammonia (NH3) or methanol (CH3OH), which are the two most discussed.

Hydrogen Carriers

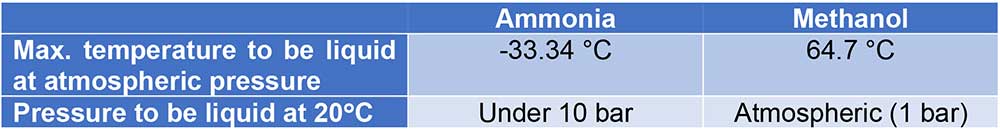

Ammonia and methanol each carry 3 atoms of hydrogen per molecule. This makes them energy-dense, i.e. lots of hydrogen per unit volume. And they are both liquid at reasonable temperatures:

Both should be kept pressurised because both are volatile: in hot weather, both can reach explosive temperatures – but that’s no different from hydrocarbon liquids and gases. Technologies for transporting both in high volumes, by both land and sea, in ships, lorries and pipelines are well known.

Both can be synthesised renewably from electricity, hydrogen and other elements that can be extracted from the atmosphere, waste, flue gases etc. However to do so adds cost over and above the cost of the hydrogen; and further energy/cost is needed to split the hydrogen from it. That further cost is avoided if it is used directly as a feedstock for the next process, e.g.

- Certain mixes of ammonia and hydrogen have very similar combustion characteristics to methane, and so can replace natural gas directly with affordable levels of modification;

- Both can be burned in suitable internal combustion engines, e.g. to power shipping;

- Both are widely used as precursor chemicals to make other substances.

Pipelines

Pipelines can be converted to carry hydrogen, provided that the pipes and seals are of suitable standard. Special pumps and valves etc. are also needed. This is because the hydrogen molecule (molecular weight = 2) is much smaller than a methane (16) or air (29). This means that what can contain methane or air may have a structure that behaves more like a sieve for hydrogen. And hydrogen can also get embedded into some materials, making it brittle (“hydrogen embrittlement”). Conversion is therefore expensive and time-consuming, though the fact that many countries have for years been replacing pipelines with ones suitable for hydrogen will reduce the time and cost of conversion. Again, the technologies are well known if not widespread.

Because the density of hydrogen gas is so low (its low molecular weight, again), it takes about 1.5 times as much hydrogen volume per unit of energy carried. But it is easily compressible. This means that a gas pipeline, suitably converted, would only carry ⅔ as much energy at full capacity and operating pressure.

Putting hydrogen into pipelines

There are two alternative ways of converting the gas grid to carry hydrogen: dilution / mixing hydrogen into the gas, and a one-off conversion to 100% hydrogen. For these, there are two primary considerations: increasing demand for hydrogen, and the uses of hydrogen.

It is important to increase demand for hydrogen, otherwise electrolysis and other hydrogen formation technologies will never have enough volume to reduce in cost. It is mooted that gas pipelines can take 5-15% hydrogen without any significant conversion of either the pipeline or the equipment that uses the gas. To that extent, dilution is of great benefit to the development of the hydrogen economy, and to the energy transition in general.

It is only in considering the uses to which the piped hydrogen would be put that we can determine the best strategy for the remainder of the transition.

Uses of hydrogen

There are many uses for hydrogen, which is why it (with electricity) is considered to be one of the two major fuels of the future; and indeed hydrogen and electricity can be combined (via synthesis) to form most of the rest, too. Hydrogen is proposed for:

- Combustion at low temperatures, e.g. domestic and commercial heating;

- Combustion at high temperatures, e.g. special industrial and chemical processes;

- Fuel cells;

- Feedstock for fuel synthesis;

- Feedstock for different chemical and industrial processes, e.g. making iron and steel.

Of these, only the first two can take a mix. And of the first two, the question must always be asked: are there cheaper or more efficient ways to achieve the result, e.g. heat pumps, arc furnaces, large-scale long-duration electricity storage (if considering combustion in power stations): in general, making hydrogen with electricity is more expensive than using the electricity directly.

Of the other uses, nearly all require pure hydrogen. Therefore putting a mix of hydrogen and natural gas in pipelines will not enable them to grow, and will therefore limit the growth of the hydrogen economy.

Another consideration is that the gas mixture at different concentrations of hydrogen will have different performance, energy density and flame characteristics, so a gradual or stepped increase in the mix may entail multiple conversions of plant and equipment, which is much more expensive and labour-intensive than a single larger conversion.

This suggests that, after the first 5-15% mixing, the remainder of the transition should be by focusing on industrial hydrogen hubs. Their pipelines will carry pure hydrogen. These pure-hydrogen pipelines can then be extended into neighbouring sections of the grid, gradually as the conversion work is done and as the availability of hydrogen increases. These hubs will therefore grow outwards until they eventually merge into large regional or national networks.

Hydrogen Storage

Hydrogen is difficult to store in large volumes. A lorry only carries typically 400kg of it (though some specialist vessels can carry up to 900kg), because of its exceedingly low density; and, for such large volumes of hydrogen, high pressures are necessary. The vessels therefore need to be made of very high grade material to avoid both leakage and embrittlement, to withstand the pressure, and to offer appropriate levels of safety.

Therefore geological storage is required, the main proposed methods being:

- Depleted hydrocarbon wells;

- Aquifers;

- Salt caverns.

Depleted hydrocarbon wells are not empty: they just have too little to be economically recoverable, typically ~35% of their original hydrocarbons. This means that, unless the hydrogen is injected and withdrawn very slowly indeed, there will be considerable mixing. Moreover, most hydrocarbons will get stuck in pores in the rock and gradually come out over time. Both of these processes contaminate the hydrogen so it can no longer be used for non-combustion purposes; and combustion would lead to low but significant levels of greenhouse gas emissions.

Moreover, for the same reason that various materials may prove porous to hydrogen that are not porous to methane, so the rocks may be also; that will need to be determined individually for each rock structure. This applies to both hydrocarbon wells and aquifers.

The best-proven way to store large volumes of hydrogen is in salt caverns. There is huge geological potential for this, the caverns are well known (currently used for both natural gas and compressed air energy storage, among other uses), though the casings and equipment (wellhead, pipes, seals, valves, pumps, safety equipment) needs to be of suitable grades.

Storing the hydrogen in salt caverns need not compete with other things being stored in them, because the geological potential is so extensive. And the pressures at which it will typically be stored are similar to the pressures of hydrogen from electrolysis, and of pipelines, so saving energy by conserving pressure.

Moreover, many applications (e.g. Storelectric’s Hydrogen CAES ™ and H2 Hybrid CAES ™, fuel/chemical synthesis, even steel making) require both hydrogen and electricity storage, so having the two in adjacent caverns makes a lot of sense. And they make even more sense when powered by intermittent renewables: such processes (and electrolysis) hate intermittency which reduces the efficiency and life of electrolysers and other process equipment, so storing the electricity near the hydrogen can deliver baseload or near-baseload energy to the process.